Are We Not Men? – 50 Years of DEVO

You can feel the anticipation in the air in the old castle courtyard in Spandau on the outskirts of Berlin. Many of the attendees (myself included) are over 50, but the age range extends down to young goth-chicks adorned in black makeup and matching Doctor Martens.

My own anticipation is mixed with a certain nervousness. I’ve never seen the band performing live before—and the three surviving members participating in this tour are now more than 70 years old. Can they actually deliver a convincing post-punk concert at this age?

DEVO emerged from one of America’s greatest traumas: the demonstrations at Kent State University, where four unarmed students were gunned down by the Ohio National Guard. Two of these were personal friends of the young Gerald Casale. Together with his fellow student Mark Mothersbaugh, he tried to articulate the experience. The result was an ironic concept that would become DEVO’s manifesto: De-evolution—the human race had simply ceased to evolve, and from now on, it would devolve instead.

The band DEVO was formed in 1973 as the musical expression of this bizarre theory—and they were post-punk even before the invention of punk. The rhythms were angular, the jarring guitar riffs so skewed that they approached the atonal, and the synthesizers didn’t play quaintly futuristic melodies —they sounded exactly like the mechanical, electronic circuits they actually were. And over it all, the enigmatic lyrics were delivered in an excited, exalted tone. Once you’ve heard their stiff, dehumanized version of the otherwise sexy “Satisfaction” by the Rolling Stones, you never forget it.

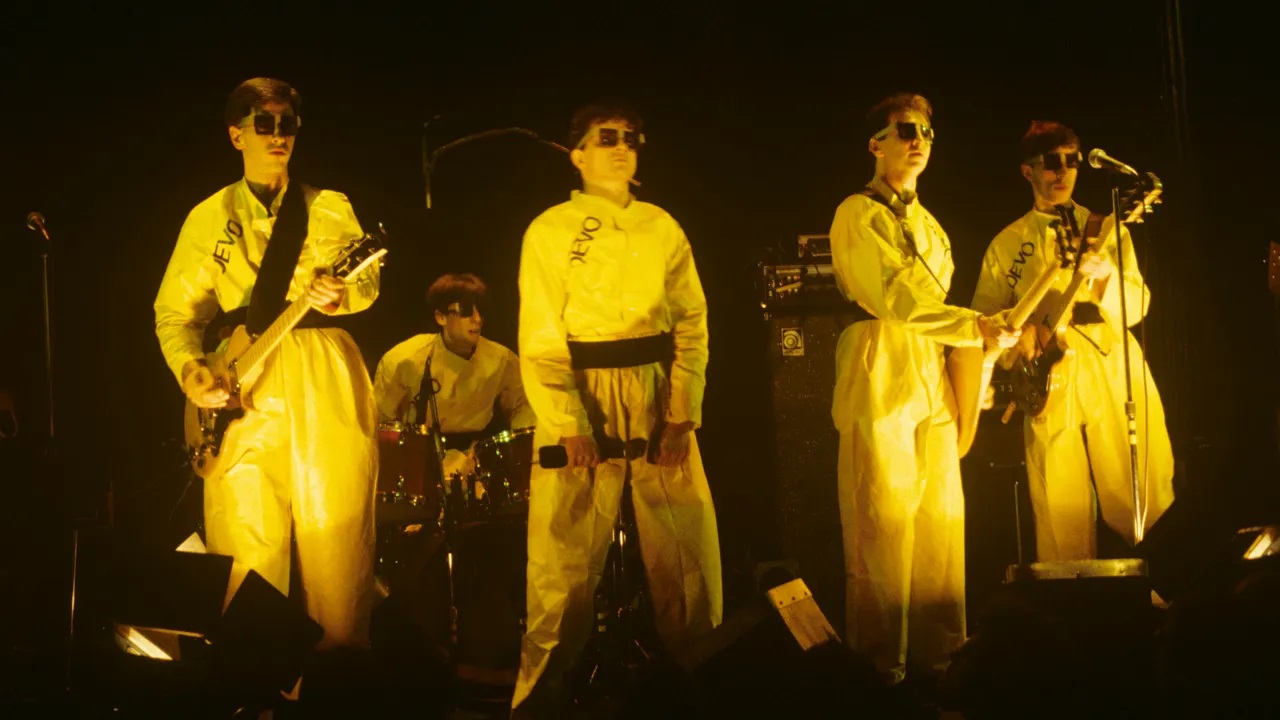

With their uniformed look and robotic movements, DEVO had the expression in place from the start. A Dane like myself can’t help but acknowledge their influence on the band Kliché (and yes, admittedly even my own band, The Neodepressionist Dance Orchestra)—but what exactly was the point? One minute they seemed to proclaim—and celebrate—their self-invented “de-evolution,” the next they skewered American everyday life with sharp social criticism. Where satire traditionally has a clearly defined point, DEVO is more like a hall of mirrors, ruthlessly distorting the entirety of human existence—from edifying, positive thinking (“Whip It”) to genetic defects (“Mongoloid”) to budding youthful sexuality (“Smart Patrol”). And “The Day My Baby Gave Me A Surprize” is either a lighthearted song about childbirth—or something far more ominous.

Based on DEVO’s reputation as both genuine originals and a solid live band, their debut album was produced by the iconic Brian Eno (in fact, even David Bowie himself had been considered as a producer). The album, quizzically entitled “Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!” (1978) includes, among other tracks, the band’s manifesto “Jocko Homo,” which already featured in their self-funded art video “The Truth about De-evolution” (1976). The band had now found its classic lineup: Founders Gerald Casale and Mark Mothersbaugh, their brothers Bob Mothersbaugh (Bob 1) and Bob Casale (Bob 2), and the ingeniously creative drummer Allan Myers.

In the early 1980s, I stumbled upon a peculiar album cover in a record store in Odense. Five men stood in a row wearing plastic uniforms with red geometric lampshades on their heads. “Freedom of Choice” (1980)—their third album—was my first encounter with DEVO. At this point, the grating punk energy had been replaced by a more polished production, and the band played tighter and more mechanically than before—a new way of musically illustration the dehumanization around which their lyrics still revolved. To quote the song “Gates of Steel”: “The beginning was the end/Of everything now/The ape regards his tail/He’s stuck on it/Repeats until he fails/Half a goon and half a god/A man’s not made of steel”.

“Freedom of Choice” surprisingly spawned DEVO’s only major hit, “Whip It,” but after a couple more albums, the creative energy seemed to fizzle out—the youthful desperation stagnating into self-parodic repetitions of predictable robot pop.

Drummer Alan Myers understandably left the project in 1986 (and unfortunately died in 2013), and the band went on hiatus in 1991. After a couple of reunions, the band finally released the surprisingly promising “Something for Everybody” in 2010. A few years later, the original lineup was further decimated by the sudden death of Bob Casale in 2014. But in 2023—on the 50th anniversary of the band’s founding—the three surviving members—augmented by two well-chosen stand-ins—embarked on their “50 Years of DEVO” tour.

And standing there on a warm August evening in the courtyard of Zitadelle Spandau, it dawns on me how much this band—that I’ve never experienced live before—has meant to me and my own musical development over the past decades: The combination of quirky experiments and catchy hooklines, revealing the cold, electronic interior of the synthesizer beneath its mask—an approach that is half rock’n’roll and half almost obsessive minimalism.

After a teasing video where an annoying A&R manager complains about this ridiculously uncompromising orchestra that just refuse to face the realities of commercialism, DEVO takes the stage. The Mark Mothersbaugh of today is an older, subdued gentleman whose voice needs warming up before reaching the ecstatic heights of the past. But decades on the road has paid off: the expression is pure, rebellious energy—and 75-year-old Gerald Casale dances his light-footed jig as 50 years ago.

With great vigour, the band blasts one classic DEVO number after another from the stage. The chronology jumps across the decades, but the audience recognizes every song, singing and cheering along. And face to face with the surviving pioneers, I finally abandon every hope of ever giving an objective review of this show. I can only surrender to the mood of enthusiastic celebration, and acknowledge the role they’ve played in my life—rejoicing in the fact that they’re still alive and kicking.

Mark Mothersbaugh enters, disguised as the eerie baby doll Booji Boy—and sings the sarcastic “Beautiful World” as an encore, before the band bids farewell, promising to see us again for their 100-year tour in 2073. They refuse to take their advanced age and inevitable death seriously. But if they did, wouldn’t they just be men—and not DEVO?

The U-Bahn train taking me home from the Zitadelle Spandau is filled to the brim with elated Berlin concertgoers.

A surprising number of whom are wearing red lampshades on their heads.

Leave a Reply